import numpy as np

import pandas as pd

import datetime as dt

from Functions import ( import_csv_BondList,

import_csv_BondTimeSeries)

import matplotlib.pyplot as plt

5-20s of the Civil War#

BondListC = import_csv_BondList('data/BondList.csv')

BondListC['First Issue Date'].head();

mask = (BondListC['First Issue Date'] > dt.datetime(1862,1,1)) & (BondListC['First Issue Date'] < dt.datetime(1872,1,1))

BondListC.loc[mask, :];

Just as battles decided the American Civil War, the outcome of the American Civil War was equally determined by differences in financing efforts. Given its unprecedented scale and duration, the Civil War cost the Union \(3.2 billion and around \)2 billion for the Confederacy, an amount which traditional sources of revenue were insufficient in meeting. Thus, while the Confederacy relied heavily on printing money, leading to rampant inflation that eroded public confidence and crippled its economy, the Union in contrast successfully leveraged a combination of taxes, the issuance of greenbacks, and most importantly bond drives which constituted two thirds of its requisite funds to create a stable and effective financial system. Most prominent amongst Union issued securities were the 5-20s bonds, which this notebook explores.

The 5-20s bonds were U.S. Treasury bonds that were issued to help finance the Union war effort, which includes supplies, equipment, and the salaries of soldiers, during the Civil War. The name “5-20s” came from the bond’s nature of maturity; that of a 20 year maturity period that could be redeemed after the span of 5 years. The 5-20s paid a 6 percent coupon, and was authorized for a total amount of 500 million dollars. Congress was able to come towards an agreement to pay coupons in specie, but left the conversation surrounding the redemption of the par value to be decided on a later date. However, it was advertised by Jay Cooke, who has exclusive access to brokering the bonds, to be redeemed with specie as opposed to lawful money (greenbacks) which traded substantially lower.

Unlike financing efforts of previous wars, the Civil War sold government debt to the public rather than conventional investors like banks or foreign nations. This was due two developments.

In the years preceding the Civil War, the federal government’s financial situation had become increasingly unstable. The Buchanan administration, which inherited a substantial surplus in the Treasury, devastated the government’s finances. When James Buchanan took office on July 1, 1857, the national debt was \(29 million, with a cash balance of \)17 million.However, the Panic of 1857, along with a tariff reduction later that year and the Southern ports’ unwillingness to send import duties to the Treasury, drastically reduced government revenue resulting in a four-year deficit. By July 1, 1860, peacetime financial liabilities had risen to nearly \(65 million, with only \)3.6 million remaining in the Treasury. When Abraham Lincoln assumed office in March 1861, the national debt had further grown to $76.4 million.

In January 1861, the government’s credit reached an all time low, compelling New York financiers to intervene by purchasing Treasury bonds and public lands just to allow the government to meet its interest payments. When Secretary Chase tried to continue the pre-war strategy of financing conflicts through loans backed mainly by financial institutions, it was unsurprising that these securities received minimal interest. The reluctance of Northern banks to invest in Union securities only intensified after a series of military defeats in 1861. One newspaper remarked that “Money lenders entertain so little confidence in the future of the United States that in order to secure loans for the use of the government its bonds must be endorsed by the individual states”. Consequently, when the government did issue securities from 1860-1861, it had to offer a high interest rate of 12 percent to attract buyers. Given this banking enviroment, the 5-20s struggled to find a market among banks, because of the scale of the debt and too low interest rates

On the other hand, there was no foreign market for the 5-20s. Many British financiers and their clients had substantial investments in the South, particularly in slavery and cotton production. As a result, they were hesitant to invest heavily in American debt during the Civil War, leading to an underdeveloped market. France exhibited similar reluctance; Napoleon III prohibited the sale of U.S. bonds on the Paris Stock Exchange and hoped for a Confederate victory, which he believed might provide a strategic ally and a buffer against a divided United States. Without backing from the financial markets in London or Paris, the U.S. faced limited foreign investment opportunities.

Under these circumstances, the 5-20s were primarily marketed to the general public. Jay Cooke, having already proven successful in selling other government securities, was granted exclusive rights to broker the 5-20s. He launched a large-scale advertising campaign, utilizing both local and national newspapers. Cooke cleverly incentivized newspapers by offering them options on bond issues, allowing editors to hold a certain amount of bonds for sixty days and profit from the transactions after deducting the interest. Cooke’s newspaper connections frequently published articles aimed at educating the public about the 5-20s, providing financial advice to a populace that had little experience with investing. In his well-known pamphlet, for instance, Cooke addressed a letter from a fictitious “Berks County Farmer,” answering practical questions with a patriotic tone.

Cooke also relied on more grassroot methods to advertise government debt, for example some advertising operations offered free coffee and donuts to those who were willing to discuss the benefits of investing in the bonds. These events specifically targeted those of the working classes who were either coming off or going on shift in the late night and early morning hours. Jay Cooke also utilized a network of over 3,000 traveling agents and sub agents who went door to door to reach potential buyers. A system was established where credit was extended to individuals, allowing them to purchase bonds (Cooke lent money to the people to purchase government debt).

In order to make the 5-20s as accessible to the public as possible, the 5-20 bonds were available in denominations as low as \(50, with the option to pay in ten installments over a five-month period. Larger denominations of \)100, \(500, \)1,000, \(5,000, and \)10,000 were also offered.

Bond Quantity#

BondQuantC = import_csv_BondTimeSeries('data/BondQuant.csv')

BondQuantC.head();

five_twenties = (20101, 'Total Outstanding')

full_period = (BondQuantC.index>dt.datetime(1862,12,1)) & (BondQuantC.index<dt.datetime(1878,12,1))

df_5_20_full = BondQuantC.loc[full_period, five_twenties].ffill() / 1e6

df_5_20_full.head();

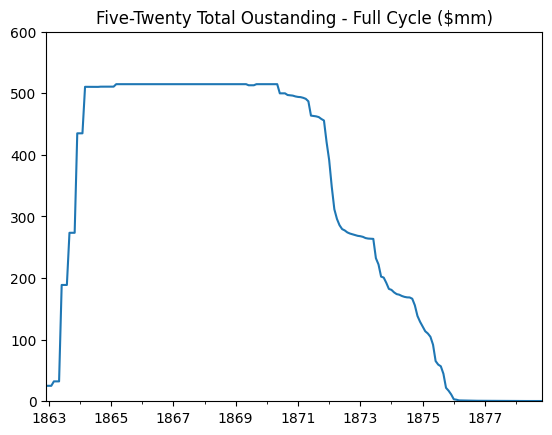

df_5_20_full.plot(title = 'Five-Twenty Total Oustanding - Full Cycle ($mm)', ylim=[0, 600]);

Initial sales were slow but picked up pace when Jay Cooke acted as a broker and advertiser, selling the bonds to the public. Starting in 1869, the government retired most of the 5-20s bonds, refinancing them with 4.5 percent, 30-year bonds and 4 percent, 15-year bonds. By 1877, all the 5-20s bonds had been redeemed.

issue_period = (BondQuantC.index>dt.datetime(1862,12,1)) & (BondQuantC.index<dt.datetime(1865,12,1))

df_5_20_issue = BondQuantC.loc[issue_period, five_twenties] / 1e6

issues = df_5_20_issue.dropna()

big = issues.diff()>10

big[dt.date(1862, 12, 31)] = True

big_issues = issues[big]

big = issues.diff()>10

ann = {

dt.datetime(1862, 11, 30): 25,

dt.datetime(1863, 3, 31): 32,

dt.datetime(1863, 6, 30): 188,

dt.datetime(1863, 9, 30): 273,

dt.datetime(1863, 12, 31): 434,

}

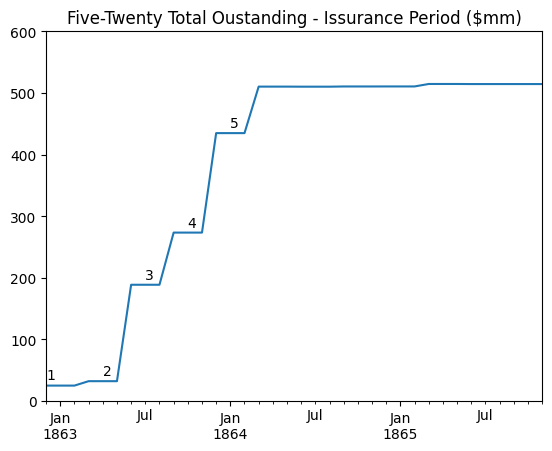

ax = df_5_20_issue.ffill().plot(title = 'Five-Twenty Total Oustanding - Issurance Period ($mm)', ylim=[0, 600]);

for i, k in enumerate(ann):

ax.annotate(i+1, (k+dt.timedelta(days=30), ann[k]+10))

February 25th - May 1st i. The 5-20s bonds were authorized for an amount of \(500 million in February 1862, but by late September only \)2.5 million worth were sold. When the 5-20s bonds were first issued, they were brokered by the government and “auctioned” to bankers. The 5-20s initially struggled to sell due to the size of the debt and the banks’ demand for higher interest rates than what the government was willing to offer. The data starts from 1863 and is a continuation of the slow trend of bond sales that began when the bonds were first issued.

May 1st - July 30th i. The Cooke brothers, through extensive lobbying, passed The National Banking Act of 1863, which required National Banks to issue notes backed by federal rather than state bonds. This created enormous demand for the 5-20s bonds in the subsequent months. ii. Jay Cooke was given exclusive access to broker the bonds, and through his 2,500 salesmen and his brother’s media connections, he marketed the debt to the public using patriotic appeals. iii. In March of 1863, public confidence was at an all-time low, and gold was increasing rapidly in price, while 5-20s were trading at 94 ½ of their par value. In response, Jay Cooke bought every bond selling below par value to boost the government’s credit. As a result, bond sales increased dramatically to a million a day. This increase in demand was so tremendous that “the great difficulty was to obtain enough bonds from the Treasury Department, which in turn was unable to get deliveries from the printers and engravers.”

July 30th - September 1st i. The Battle of Gettysburg was a turning point in the war in favor of a Union victory. Investors likely saw the 5-20s as a safer investment. ii. On July 1st, 1863, legal tender notes could no longer be converted into 5-20s. During that same time period, newspapers around the country, but predominantly those owned and influenced by the Cooke brothers, began to frame buying the 5-20s as the “last chance” to cash in on such a deal.

September 1st - April 1st i. There was a succession of Union victories from September 1863 until the year’s end.

Some important notes to consider#

Pulling the strings behind the issuance and brokerage of the 5-20s bonds was Jay Cooke. The success of the 5-20s in raising war-time money is often credited to Salmon P. Chase, however it was Cooke who through intensive lobbying, put Chase in office, and later on Senator Sherman, both who were instrumental in not only creating the 5-20s bonds, but also in passing key bills that facilitated the sale of the bond.Cooke was the mastermind who put political figures into office so that he could profit off the commission of sales (Abernathy).

In a letter to a prospective investor, Jay writes “Congress has provided that the Bonds shall be PAID in Gold when due”. The 5-20s were advertised to be redeemed for its par value in gold.

active_mask = BondQuantC.columns.get_level_values('Series') == "Active Outstanding"

outstanding = BondQuantC.loc[:, active_mask]

agg = outstanding.sum(axis=1)

Bond Price#

BondPriceC = import_csv_BondTimeSeries('data/BondPrice.csv')

five_twenties_price = BondPriceC.loc[(BondPriceC.index>dt.datetime(1862,12,1)) & (BondPriceC.index<dt.datetime(1878,12,1)), (20101, 'Average')]

prices = BondPriceC.mean(axis=1)

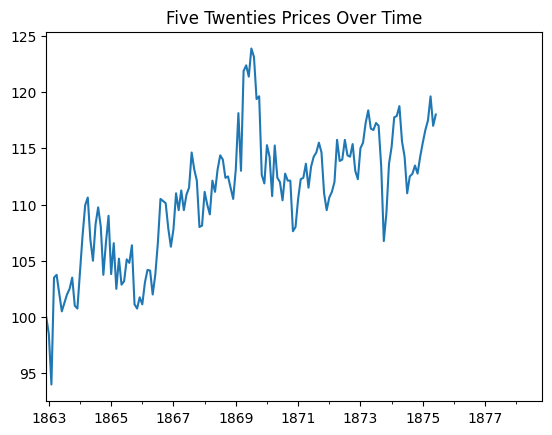

five_twenties_price.plot(title='Five Twenties Prices Over Time');

In the first few years upon issuance, the climb in prices was because the 5-20s were seen as a method of currency exchange (it could be purchased in Greenbacks but was advertised to be redeemable in gold). Thus as the value of greenbacks relative to gold depreciated, the prices of 5-20s rose. In later years, starting from the 1870s, interest rates fell, which made the 5-20s a more attractive investment.

In 1869, the Public Credit Act was passed, clarifying the uncertainty over whether the 5-20 bonds would be redeemed in gold or greenbacks. Because gold was considered more valuable compared to greenbacks the bonds became even more desirable, driving up their prices.

The Panic of 1873 led to widespread bank failures. As banks collapsed, the financial system became unstable, leading to a lack of confidence in various financial instruments, including government bonds. The panic also triggered a stock market crash, which caused investors to liquidate assets rapidly, including “five-twenties” bonds, to cover losses and maintain liquidity.

five_twenties_price2 = BondPriceC.loc[issue_period, (20101, 'Average')]

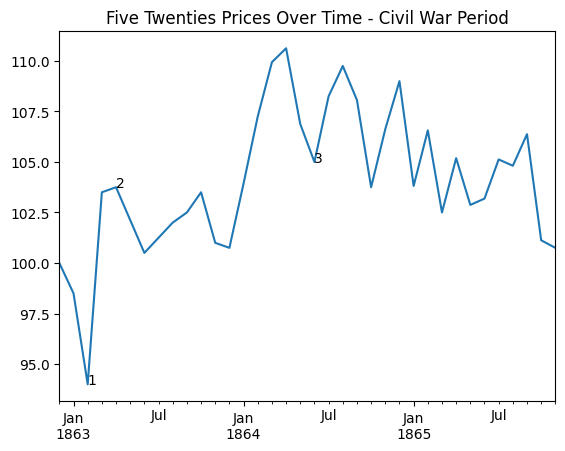

ax2 = five_twenties_price2.plot(title='Five Twenties Prices Over Time - Civil War Period');

x = [

dt.datetime(1863, 2, 28),

dt.datetime(1863, 4, 30),

dt.datetime(1864, 6, 30),

]

for i, d in enumerate(x):

ax2.annotate(i+1, (d, five_twenties_price2[d]))

On January 8 1863 it was made public that Congress had increased the supply of Greenbacks by $300 million. This increase in greenback supply would likely lead to inflation, reducing the value of greenbacks relative to specie. Since 5-20 bonds could be bought in greenbacks, and was advertised to be redeemable in specie, their relative value would increase as the value of greenbacks decreased.

On April 27, 1863, the Confederate Treasury Note Act was passed, which authorized the issuance of interest-bearing Treasury notes, known as “Six Per Cent Non-Taxable Bonds.” This, coupled with a series of Union defeats in April such as the Battle of Plymouth, as well as tumultuous political developments in the Union like the Proclamation of Amnesty and Reconstruction that caused unrest, could have resulted in investors preferring Southern bonds and thus crowding out investment for the 5-20s in foreign markets.

On June 3, 1864, the National Banking Act was signed with revisions from the earlier Act of 1863. The difference was a result of a combination of pressure from elite banker Jay Cooke and revisions in the 1863 Act, which forced New York City banks—holding a lion’s share of the country’s capital—to comply with the Act, increasing demand for the 5-20s substantially.

Some observations#

Interestingly, bond prices seem to be more sensitive towards developments in government actions or in the finance industry as opposed to developments in the war, with the exception of the Battle of Gettysburg. That is because regardless of the outcome of the war, the Union was going to persist, with or without the Confederate States. But the Battle of Gettysburg was the first well publicized turning point in a war that was previously in a stalemate. This victory signaled to investors that the war was progressing faster which meant the government could sooner stop borrowing and start paying back investors.

One of the biggest incongruencies on the graph that we are still investigating, is Early’s failed raid on the White house. Jubal Early’s army reached within five miles of the White House by July 11th. This created an uproar among Union states, the Washington Evening Star on July 10th wrote “The excitement in this city is intense and on the increase. Crowds are thronging the bulletin boards, and a thousand wild and improbable rumors are in circulation”. We know that this news struck deep within the financial community, because this resulted in the largest shift of the entire war for Greenbacks, a change of 4.8 percent which dwarfed the next largest 2.6 percent.

Who wanted the 5-20s to be redeemed in gold?#

The issue of national debt became central to the Republicans’ electoral strategy for the 1866 midterm elections. Union General Benjamin Butler cautioned Massachusetts voters that if democrats were to be elected “What would your 7:30s [and 5-20s] be worth?”. Perhaps most vocal among those who wanted the 5-20s to be redeemed in gold, was prominent banker Jay Cooke. While acting as a salesman, Jay Cooke advertised that “Congress has provided that the Bonds shall be PAID in Gold when due”. With his reputation on the line, it is most likely that Mr Cooke used his numerous political and media connections to promote legislation that mandated government bonds to be paid back in gold.

Who wanted 5-20s to be redeemed in Greenbacks?#

The push to redeem the 5-20s in greenbacks rather than gold came primarily from the Western states. The Western economy, heavily dependent on agriculture, faced a chronic scarcity of gold and specie, worsened by the war, as much of the hard currency had been drained to the East or out of circulation, creating a credit crunch. The economic struggles were made worse by crop failures, competition with older agricultural regions, and manipulative railroad rates controlled by Eastern interests.

In this context, Western farmers and debtors, alongside populist and radical factions within the Democratic Party, saw the redemption of bonds in greenbacks as a practical solution to their financial troubles. By redeeming bonds with greenbacks, the government would inject additional money into the economy. Because greenbacks were not supported by gold, printing more of them would lead to a rise in the total money supply. This increase in money flow would supply essential liquidity to an economy lacking in hard currency.

Moreover, many Westerners, particularly farmers, were deeply in debt. They owed money in the form of mortgages and loans that had to be repaid in hard currency. If the government redeemed the bonds in gold, it would drive up the value of gold relative to greenbacks, further increasing the debt burden. By redeeming the bonds in greenbacks, which were less valuable than gold, the debtors would effectively reduce the amount they owed in real terms, easing their financial pressures.

The movement to redeem the 5-20s with Greenbacks eventually expanded beyond the Western states, evolving into a broader critique of wealth creation, questioning the relationship between labor, land, and the financial sector, which many believed profited without contributing real work. Critics argued that the creation of a permanent national debt was a system designed around benefiting wealthy investors and financial institutions at the expense of ordinary citizens. These “bondocrats,” as they were derisively called, held substantial portions of the debt and were seen as profiting from government-backed guarantees of interest payments at the expense of high taxes on the poor and middle class. President Andrew Johnson even suggested that interest payments could count toward repaying the bond principal.

How were the 5-20s ultimately redeemed?#

To manage the financial challenge of redeeming the 5-20s, taxes and custom duties were used to make interest payments and create a budget surplus, which helped reduce some of the debt and establish a sinking fund for future repayment. However, taxation alone was not enough to fully repay the debt, especially given public opposition to certain taxes.

Fortunately, U.S. securities were in high demand on international markets, which allowed the government to refinance its existing debt. In the summer of 1865, rising tensions over a potential war between Germany and France, along with the strong support of German Americans who felt a deep connection to their homeland, fueled this demand. Many German Americans viewed the Southern aristocracy’s attempt to dismantle the American republic as a parallel to the military coups in the German states in 1848 that had crushed the democratic movement in Europe. Opposed to slavery, they had established abolition societies in the 1850s, and the German-language press consistently denounced the institution. For these Germans, investing in America’s financial stability was a way to show solidarity with the American anti-slavery cause.

Growing interest in American Securities within European markets gave Congress the flexibility to pass the Public Credit Act, which required government bonds to be redeemed in more costly specie instead of Greenback. Although the Public Credit Act was passed in March 1869, it wasn’t until a year later, under Treasury Secretary George Boutwell, that Congress began to seriously address refinancing the debt. The Public Credit Act, which restored investor confidence, reducing the risk premium of U.S. securities, allowed for the Treasury to issue \(500 million in 10-year bonds at 5 percent, \)300 million in 15-year bonds at 4.5 percent, and $1 billion in 30-year bonds at 4 percent starting July 14th 1870. By 1877, all 5-20 bonds had been completely redeemed.

Conclusion#

The issuance and subsequent redemption of the 5-20s bonds during and after the Civil War were pivotal in stabilizing Union finances and ensuring the nation’s economic recovery. These bonds not only set a precedent for future government debt management but also bolstered public confidence in U.S. financial credibility on a global scale. The success of the 5-20s bonds had long-term implications in introducing innovative fiscal policy decisions during times of crisis.

Citations#

Adams, John. “International Bond Sales during the American Civil War.” The John Adams Institute, September 15, 2022. https://www.john-adams.nl/international-bond-sales-during-the-american-civil-war/.

Adams, John. “The Most Democratic Bond Issue of the War.” The John Adams Institute, September 22, 2022. https://www.john-adams.nl/the-most-democratic-bond-issue-of-the-war/.

Chester McA. Destler. “The Origin and Character of the Pendleton Plan.” The Mississippi Valley Historical Review 24, no. 2 (1937): 171–84. https://doi.org/10.2307/1892077.

Newman, Patrick. “The Origins of the National Banking System: The Chase—Cooke Connection and the New York City Banks.” The Independent Review 22, no. 3 (2018): 383–401. http://www.jstor.org/stable/26314773.

Cooke, Jay. Letter of Mr. Jay Cooke on the payment in gold of the U. S. five-twenty bonds. Dated. 1868. Pdf. https://www.loc.gov/item/96186382/.

Oberholtzer, Ellis Paxson. Jay Cooke, financier of the Civil War. vol. 1. New York: Kelley, 1968. Newman, P. (2018). “The Origins of the National Banking System: The Chase-Cooke Connection and the New York City Banks.” The Independent Review, 22(3), 383-401. Published by Independent Institute. Retrieved from JSTOR.

Rothbard, M. N. (2002). History of Money and Banking in the United States: The Colonial Era to World War II. Ludwig von Mises Institute. Retrieved from Mises Institute.

Wikipedia contributors. “Economic history of the American Civil War.” Wikipedia, The Free Encyclopedia, 2024. Available at Wikipedia.

Abernathy, C., et al. (2018). “Reconstruction.” The American Yawp, Stanford University Press. Available at The American Yawp.

Abernathy, C., et al. (2018). “The Civil War.” The American Yawp, Stanford University Press. Available at The American Yawp.

Bayley, R. (1869). “The National Debt of the United States.” Economic Journal, 29(2), 220-240. Retrieved from your Dropbox.

Foner, E. 1988. Reconstruction: America’s Unfinished Revolution, 1863–1877. New York: HarperCollins Publishers.

Blight, D. 2001. Race and Reunion: The Civil War in American Memory. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Higgs, R. 1987. “Crisis and Leviathan: Critical Episodes in the Growth of American Government.” New York: Oxford University Press.

McPherson, J. M. 1988. Battle Cry of Freedom: The Civil War Era. New York: Oxford University Press.

Ransom, R. L. (1989). Conflict and Compromise: The Political Economy of Slavery, Emancipation, and the American Civil War. Cambridge University Press.

Richardson, H. C. (2001). The Death of Reconstruction: Race, Labor, and Politics in the Post–Civil War North, 1865–1901. Harvard University Press.

Studenski, P., & Krooss, H. E. (1952). Financial History of the United States. McGraw-Hill Book Company, Inc.

Mitchell, B. R. (1962). Abstract of British Historical Statistics, Cambridge University Press. (For comparative analysis of post-war economies.)